Defamiliarization

“We get used to horrible things and stop fearing them. We get used

to beautiful things and stop enjoying them. […] Art is a means to make things

real again” (Shklovsky, “Art, as Device” 151).

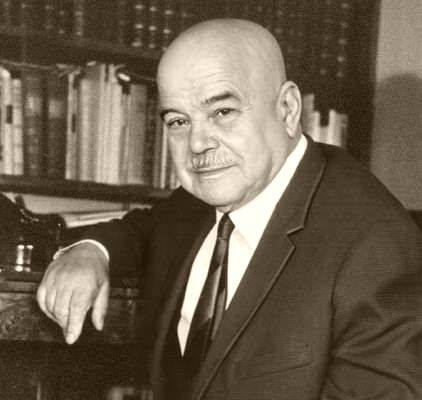

Viktor Shklovsky introduced the technique

of ostranenie, which translates to “estrangement”. He first introduced

the term in his article, Art, as Device, in 1917. Ostranenie is more

commonly known as defamiliarization. In his book, Theory of Prose(1925), he defines defamiliarization as “the removal of an object from the

sphere of automatized perception” (6). In Art, as Device, Shklovsky

argues that art exists “to return back the sensation to life – or, more

probably, of life” (154). He later goes on to explain how things have

become insignificant in automatized life and claims that art is what brings

back this significance.

Shklovsky, along with other formalists, focused

on the application of defamiliarization in poetry. They claimed that the

technique of defamiliarizing prolonged the process of how a person perceived

what was being read. Shklovsky and other formalists, like Roman Jakobsen,

believed that the main obstacle we face is automatization. Jakobsen talked

about how the perception we hold of the things around us becomes automated,

which means that we get used to them to the point where what we do and see

becomes automatic; this impedes us from being aware of what is around us. If

automated perceptions are defamiliarized, we can remove the blinds we have on

(metaphorically) and see again.

Symbolists believed that thoughts arise from the subconscious,

which makes it easier to fall into the habit of automatization, because

physical actions, after much reverberation, become habitual. Just as formalists argued,

routine actions become automatic and no longer stimulate. “The purpose of art is to impart the sensation of things as they are

perceived and not as they are known.” (Shklovsky, “Art as Technique” 2).

The approach of defamiliarization in the framework of furniture promotes

a change in how we experience objects. It is essential in this context in order

to communicate the value of design. When objects are placed out of their normal

circumstance, we can try to apprehend them as abstract forms in lieu of using

their familiarity to associate them. By doing so, it encourages a new form of

interaction that elevates the experience, pressed by the need to refine the way

design is approached.

In Shklovsky’s

article Différance

in Defamiliarization, he defines the

technique of defamiliarization as “a restoration of difference to an object

which has “lost” it in the course of a life” (211). Viktor Shklovsky refers to

Leo Tolstoy, who was a Russian writer in the late 19th and early 20th

century, in this same article on how in order to take an object out of its

“habitual recognition” he would defamiliarize it through an objective

description. Instead of referring to an object by how we know it to be called,

he describes it as if he has come across it for the first time. When an object

is referred to in a context that is unfamiliar, it can be presented and

perceived in a renewed way. If objects are “deconstructed” and “reassembled” into a new form, taken

apart and recombined in a manner of visual practice, they can obtain a new

demeanor even though they are familiar in certain aspects. Once the viewer

learns to approach a form objectively, they can separate a whole to analyze its

parts and then reassemble it, but with emotion incorporated into it. The result

is a more developed version and the combination of subject and object through

an obscure and dreamlike method. In a sense, this transforms objects into a

particular level of abstraction, where it begins to blur the line between art

and design.

The idea was to carefully defamiliarize an object to where

it would be interpreted and perceived as new, but not to the extent where it became completely unrecognizable. One of the goals of defamiliarization, as argued by

Shklovsky in Art, as Device, is to prolong an object’s perception enough

to the point that it is experienced continually. Presenting familiar objects in an unfamiliar way can instigate a

reaction from the users. Taking something familiar and distorting its physical

appearance, function, or decontextualizing it can make it become more prominent. The concentration of the objects in such a curated space encourages

the ultimate absorption of them. The objects become a poetic form by being

presented as an abstraction of functionality.